Part 3: Symptoms and Diagnosis

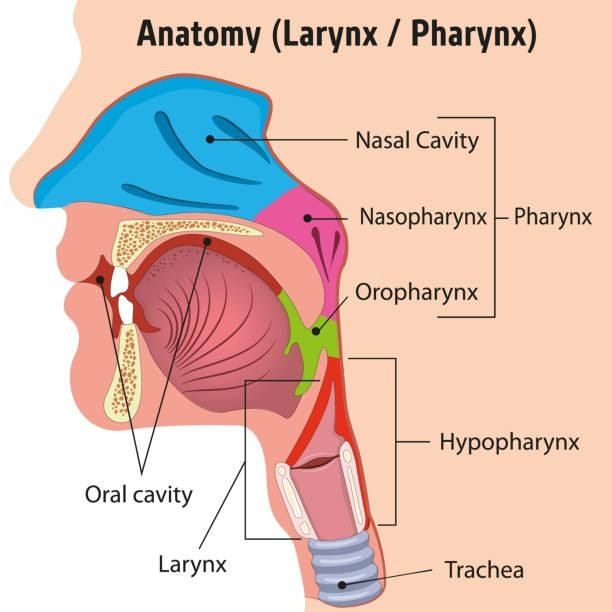

NPC is a bit of a stealth cancer. The nasopharynx is a hidden chamber behind your nose and above the throat, so tumors can grow quietly for months.

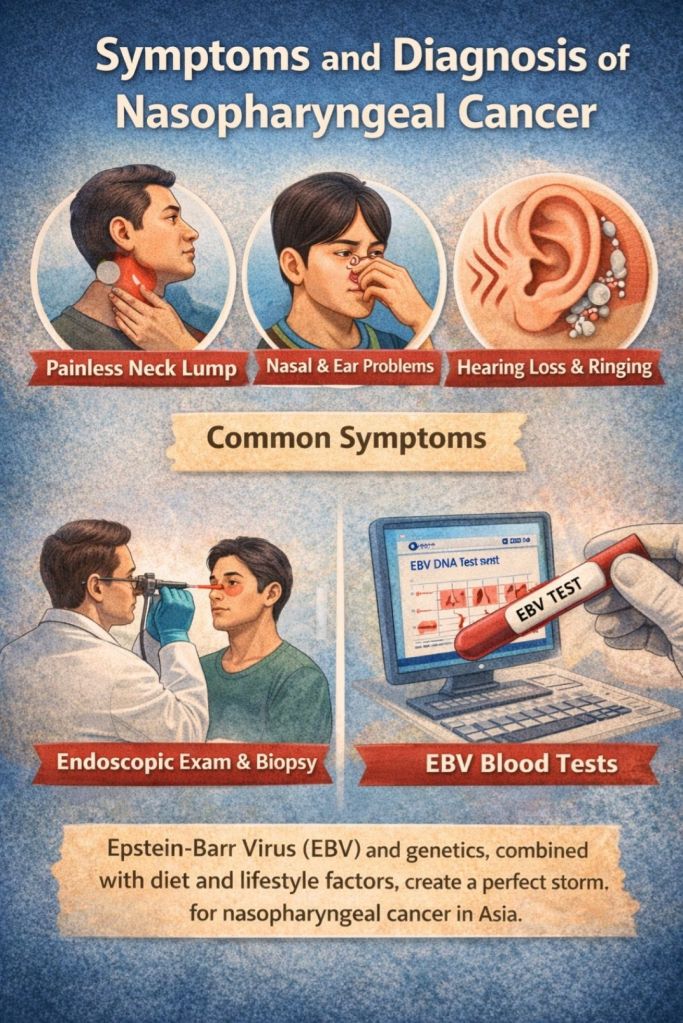

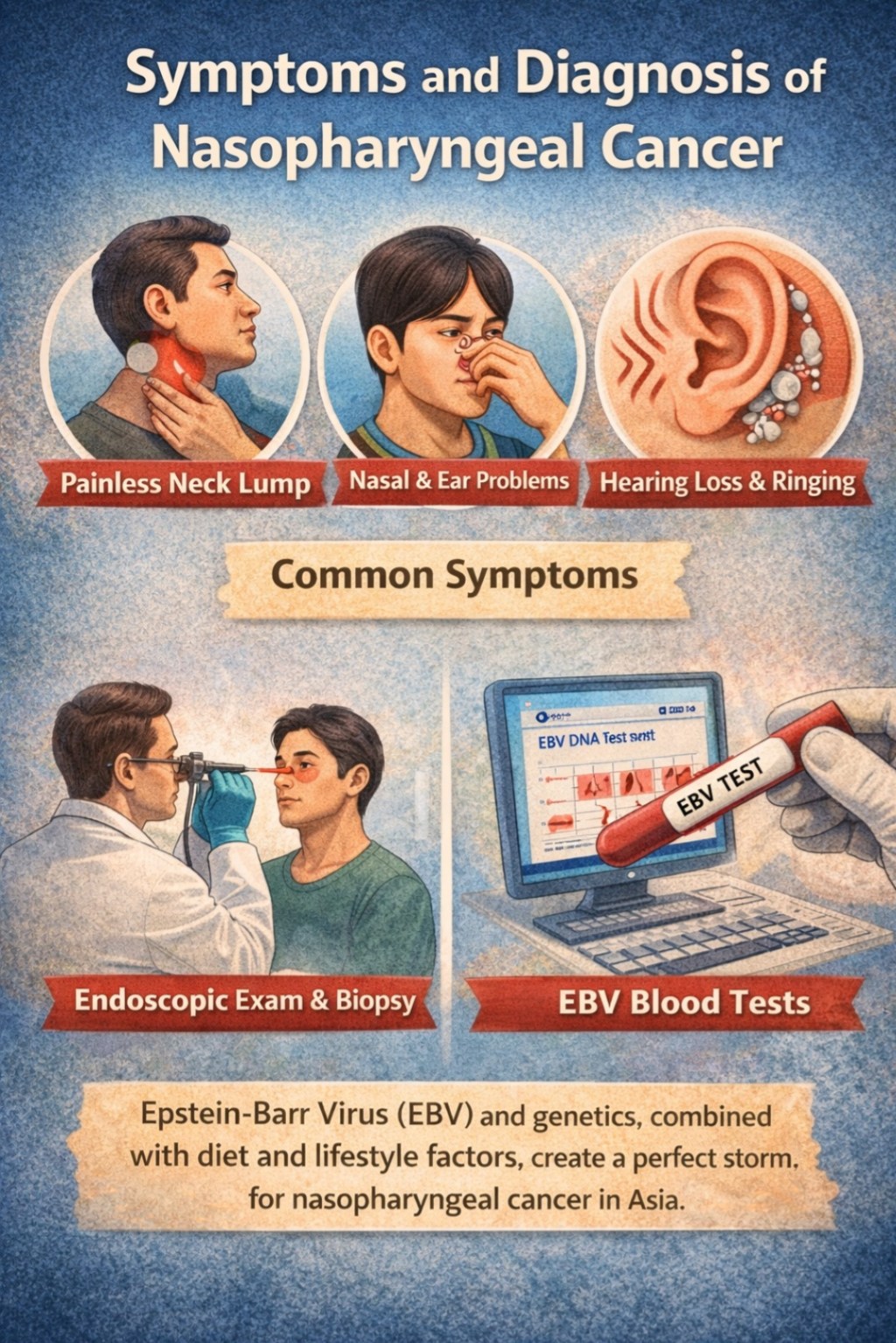

Often the very first hint is something seemingly minor: a stuffy nose on one side that won’t go away, or an occasional nosebleed. These early signs feel like common sinus problems, so they’re easy to overlook. Many patients actually ignore them, assuming it’s just allergies or a minor infection.

Then comes the telltale clue – a neck lump.

Yes, the most common sign of NPC is a painless mass in the neck from a swollen lymph node. It’s the cancer sending an SOS signal. In fact, classic studies (and surgical training) note that enlarged cervical lymph nodes often prompt the diagnosis. A 1941 report from Hong Kong even described patients who first noticed neck nodes and ear symptoms, and today that’s still true. Think of it like weeds growing underground suddenly pushing up a shoot – the gland feels odd, and then doctors see it.

Ear problems are another big clue. Because the tumor sits by the eustachian tube, it can block fluid drainage and cause chronic ear fullness or hearing loss. Patients sometimes get recurrent “glue ear” that doesn’t clear, especially on one side – a red flag in adults. Some describe muffled hearing, ringing (tinnitus), or even sudden deafness. It’s almost as if the cancer plugs up your ear canal from the inside.

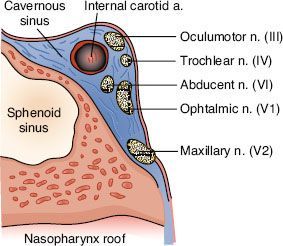

Less commonly, NPC can invade nearby nerves. This might produce double vision, facial numbness, or headaches if cranial nerves are involved. (Rarely, syndromes like Gradenigo’s or Vernet’s – technical names involving eye and ear nerves – can appear first.) But neurologic symptoms generally mean a later stage: by then the tumor has spread within the skull base. Early on, neck and ear signs dominate.

Diagnosing NPC takes a bit of detective work. If NPC is suspected (say, an Asian patient with a neck node and nose symptoms), the first step is an endoscopic exam. Doctors use a thin, flexible nasoscope (a camera-tipped tube) to look deep into the nasal cavity and nasopharynx. They’re looking for any abnormal lump, ulcer, or mass. If something suspicious is seen, a biopsy is taken from the nasopharyngeal wall. Often a biopsy of the neck lymph node is done too. In fact, NPC can be confirmed via a fine-needle aspirate (FNA) of the neck node, or a direct tissue biopsy. Pathologists then identify nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells.

Imaging is also key. Every patient with confirmed NPC gets a CT or MRI scan (or both). A CT scan shows how the cancer affects bone structures around the skull base, while MRI gives the best picture of soft tissue. Think of MRI as your high-definition surveillance: it maps exactly how far the tumor extends into surrounding areas (and it’s essential for planning radiation therapy). In modern centers, we often fuse endoscopy with MRI and CT so radiation oncologists can contour the tumor precisely. Better imaging has dramatically improved outcomes, because we can now “paint” radiation more accurately on the tumor shape.

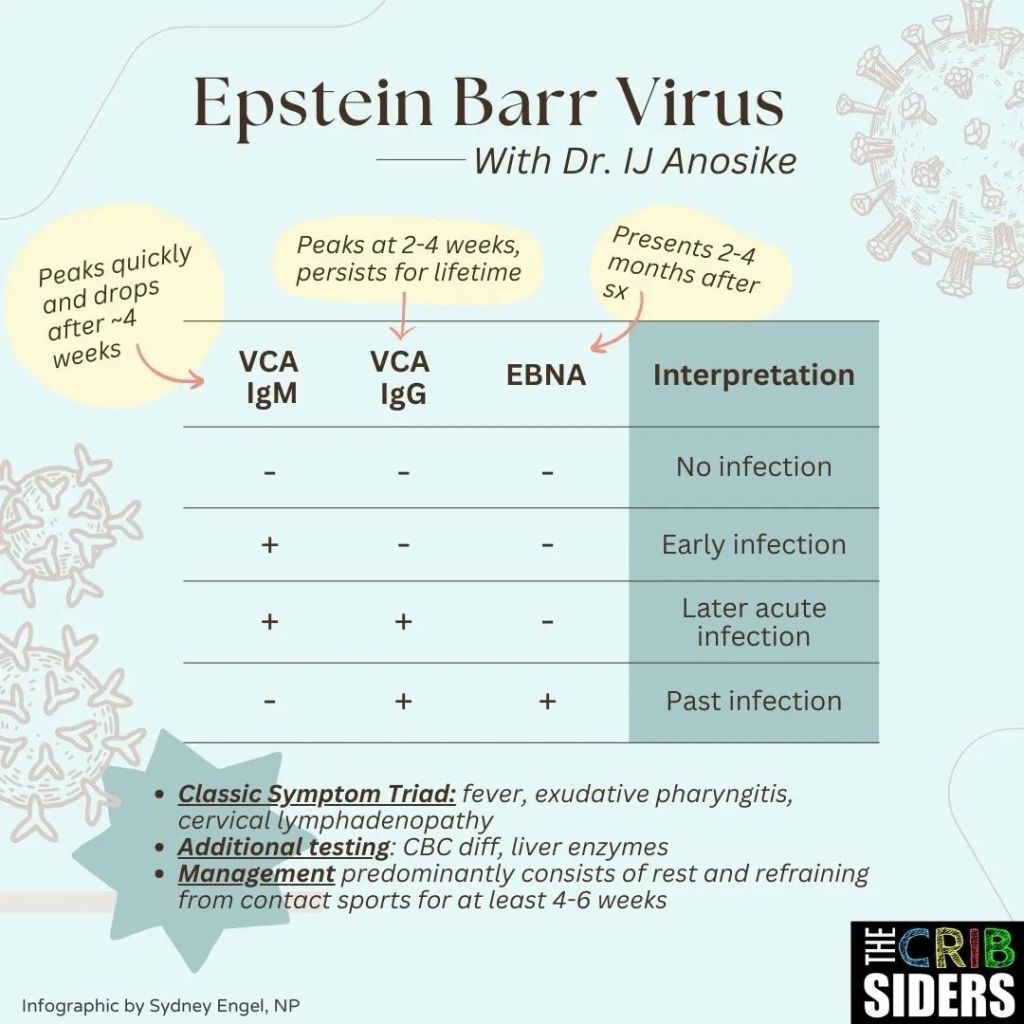

Finally, there are screening tests for high-risk people. In endemic regions, doctors sometimes check blood for EBV markers. In Hong Kong, for instance, at-risk adults get blood tests for EBV-related antibodies (IgA to viral capsid antigen and EBNA1). If the test is positive, the patient is sent for endoscopy and imaging. These efforts catch some cancers early.

A recent innovation is to add a quick MRI scan whenever the EBV test is positive: in one study, this “shotgun MRI” found early tumors that endoscopy had missed. The upshot? In EBV-screened patients, MRI boosted early detection and confidence that nothing was hiding. As one study put it, adding even a short, contrast-free MRI is a clever way to catch “occult” NPC.

Leave a comment